I am avid reader of John Hussman and eagerly await his weekly commentary on the markets, economics, and investing climate. Professor Hussman's pieces are usually a good read, but I have to say his latest commentary knocks it out of the park. An excerpt of the piece can be found below and the remainder can be found here

Before the 15th century, people gazed at the sky,

and believed that other planets would move around the Earth, stop, move

backwards for a bit, and then move forward again. Their model of the

world – that the Earth was the center of the universe – was the source

of this confusion.

Similarly, one of the reasons that the economy

seems so confusing at present is that our policy makers are following

models that have very mixed evidence in reality. Worse, when

extraordinary measures don’t produce the desired results, the response

is to double the effort without carefully asking whether there is a

reliable, measurable cause-and-effect relationship in the first place.

When there are broken links in the chain of cause-and-effect, “A causes

B” may be true, and “C causes D” may be true, but if B doesn’t cause

C, then all the A in the world won’t give you D.

Let’s review some relationships in the data that are clear, and some that are not so clear at all.

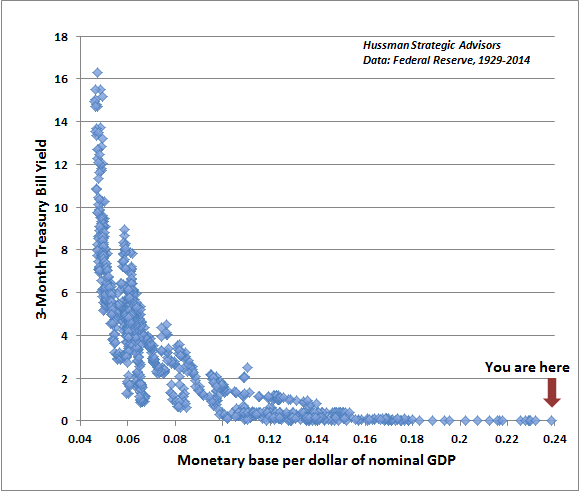

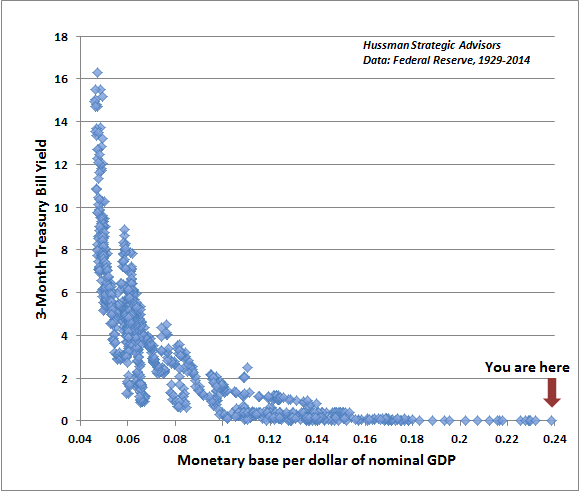

Quantitative easing and short-term interest rates

First, the following chart shows the relationship

since 1929 between the monetary base (per dollar of nominal GDP) and

short-term interest rates. This is our variant of what economists call

the “liquidity preference curve,” and is one of the strongest

relationships between economic variables you’re likely to observe in

the real world. After years of quantitative easing, the monetary base

now stands at 24% of GDP. Notice that less than 16% was already enough

to ensure zero interest rates, so the past trillion and a half dollars

of QE have done little but increase the pool of zero-interest assets

that are fodder for yield-seeking speculation. Notice also that unless

the Fed begins to pay interest to banks on their idle reserves, the Fed

would have to contract its balance sheet by about $1 trillion

just to raise Treasury bill yields up to a fraction of one percent. So

the primary policy tool of the Fed in the next couple of years will

likely be changes in interest on reserves (IOR). Get used to that

acronym.

No comments:

Post a Comment