Monday, November 25, 2013

High Prices Beget Higher Prices- Price/Volume Heat Map for Nov. 22

It should probably go without saying that I remain bearish overall. The economy remains weak, profit margins are abnormally high, and the investment/economic environment continue to be manipulated by the Federal Reserve's money printing/bond buying train. That said, it has been my observation that higher prices beget higher prices and the S&P 500 closing at an all-time high- following the Dow Jones- suggests equity prices will continue to trend higher. For how long is anyone's guess, as overall volume levels remains subdued and demand (as evidenced by the price/volume heat maps below) has become mixed. With that said, I would not expect us to get any definitive answers in this week's trading, considering the Thanksgiving holiday in the US.

Looking at the latest daily heat map, we are seeing a few divergences. For instance, the discretionary price performance versus demand.

Week Ending Nov. 22

For the latest ended week, the S&P 500 closed marginally higher, but it was enough to push the index to all time highs.

That said, demand appears weak overall and the weekly performance was limited in scope.

Looking at the latest daily heat map, we are seeing a few divergences. For instance, the discretionary price performance versus demand.

Week Ending Nov. 22

For the latest ended week, the S&P 500 closed marginally higher, but it was enough to push the index to all time highs.

That said, demand appears weak overall and the weekly performance was limited in scope.

A Glimpse of the Monetary Hot Potato- A Fee on Your Deposits

As I showed here, Mises described the three step process in which money printing can (at least in the first step) lead to a lower velocity of money, as the demand for money increases, helping maintain the purchasing power of the dollar. Moving into the second and third step would take some event or series events that would cause businesses and individuals to decrease their demand to hold money.

We may have just seen the first signs that these later phases are closer than many believe or understand. In the latest Fed minutes from the October meeting, the Federal Reserve board openly discussed the idea of cutting the interest rates on reserves kept with the Fed that it pays to the banking system. As most investors and the media fawned all over the idea of taper occurring sooner rather than later, this announcement was largely ignored. More so and in response a number of banking concerns discussed charging depositors a fee for deposits kept by the banks. This is discussed here in an article by the FT.com

Depositors already have to cope with near-zero interest rates, but

paying just to leave money in the bank would be highly unusual and

unwelcome for companies and households.

The warning by bank executives highlights the dangers of one strategy the Fed could use to offset an eventual “tapering” of the $85bn a month in asset purchases that have fuelled global financial markets for the last year.

Banks say they may have to charge because taking in deposits is not free: they have to pay premiums of a few basis points to a US government insurance programme.

“Right now you can at least break even from a revenue perspective,” said one executive, adding that a rate cut by the Fed “would turn it into negative revenue – banks would be disincentivised to take deposits and potentially charge for them”.

Other bankers said that a move to negative rates would not only trim margins but could backfire for banks and the system as a whole, as it would incentivise treasury managers to find higher-yielding, riskier assets.

“It’s not as if we are suddenly going to start lending to [small and medium-sized enterprises],” said one. “There really isn’t the level of demand, so the danger is that banks are pushed into riskier assets to find yield.”

The danger of negative rates has deterred the Fed from cutting interest on bank reserves in the past. If it were to do so now, it would most probably expand a new facility that lets banks and money market funds deposit cash at a small, positive interest rate. That should avoid any need for banks to charge depositors.

About half of the reserves come from non-US banks that do not have to pay the deposit insurance fee. Their favourite manoeuvre is to take deposits from money market funds and park them overnight at the Fed, earning millions of dollars risk-free. Cutting the interest on reserves would stop that.

Lowering interest on reserves would also affect money market funds, said Alex Roever, head of US interest rate strategy at JPMorgan.

“[It] would decrease the incentive for those banks to borrow in the money markets, which in turn could leave money market funds short of certain investments and force them to bid up the price of their next best options,” he said.

Richard Gilhooly, strategist at TD Securities, highlighted some benefits to the Fed from the possible cut: “[It] would not only anchor short-term rates near zero, it also stands to boost the profits for the Fed as they pay less interest to banks,” he said.

Have no doubt, a reduction in the interest rates banks receive for holding reserves at the Fed will reduce the amount of reserves banks are holding on their balance sheets. Additionally, a fee on deposits will likely lead to businesses and individuals draining their saving deposits from banks, reducing the demand to hold money and increasing the velocity of money.

Although it remains uncertain if the Fed will cut rates on reserves or banks will start fees on deposits, this is a road sign to watch.

We may have just seen the first signs that these later phases are closer than many believe or understand. In the latest Fed minutes from the October meeting, the Federal Reserve board openly discussed the idea of cutting the interest rates on reserves kept with the Fed that it pays to the banking system. As most investors and the media fawned all over the idea of taper occurring sooner rather than later, this announcement was largely ignored. More so and in response a number of banking concerns discussed charging depositors a fee for deposits kept by the banks. This is discussed here in an article by the FT.com

Leading US banks have warned that they could start charging companies and consumers for deposits if the US Federal Reserve cuts the interest it pays on bank reserves.

The warning by bank executives highlights the dangers of one strategy the Fed could use to offset an eventual “tapering” of the $85bn a month in asset purchases that have fuelled global financial markets for the last year.

Minutes of the Fed’s October meeting

published last week showed it was heading towards a taper in the coming

months – perhaps as soon as December – but wants to find a different

way to add stimulus at the same time. “Most” officials thought a cut in

the interest on bank reserves was an option worth considering.

Executives at two of the top five US banks said a cut in the 0.25 per

cent rate of interest on the $2.4tn in reserves they hold at the Fed

would lead them to pass on the cost to depositors.Banks say they may have to charge because taking in deposits is not free: they have to pay premiums of a few basis points to a US government insurance programme.

“Right now you can at least break even from a revenue perspective,” said one executive, adding that a rate cut by the Fed “would turn it into negative revenue – banks would be disincentivised to take deposits and potentially charge for them”.

Other bankers said that a move to negative rates would not only trim margins but could backfire for banks and the system as a whole, as it would incentivise treasury managers to find higher-yielding, riskier assets.

“It’s not as if we are suddenly going to start lending to [small and medium-sized enterprises],” said one. “There really isn’t the level of demand, so the danger is that banks are pushed into riskier assets to find yield.”

The danger of negative rates has deterred the Fed from cutting interest on bank reserves in the past. If it were to do so now, it would most probably expand a new facility that lets banks and money market funds deposit cash at a small, positive interest rate. That should avoid any need for banks to charge depositors.

About half of the reserves come from non-US banks that do not have to pay the deposit insurance fee. Their favourite manoeuvre is to take deposits from money market funds and park them overnight at the Fed, earning millions of dollars risk-free. Cutting the interest on reserves would stop that.

Lowering interest on reserves would also affect money market funds, said Alex Roever, head of US interest rate strategy at JPMorgan.

“[It] would decrease the incentive for those banks to borrow in the money markets, which in turn could leave money market funds short of certain investments and force them to bid up the price of their next best options,” he said.

Richard Gilhooly, strategist at TD Securities, highlighted some benefits to the Fed from the possible cut: “[It] would not only anchor short-term rates near zero, it also stands to boost the profits for the Fed as they pay less interest to banks,” he said.

Have no doubt, a reduction in the interest rates banks receive for holding reserves at the Fed will reduce the amount of reserves banks are holding on their balance sheets. Additionally, a fee on deposits will likely lead to businesses and individuals draining their saving deposits from banks, reducing the demand to hold money and increasing the velocity of money.

Although it remains uncertain if the Fed will cut rates on reserves or banks will start fees on deposits, this is a road sign to watch.

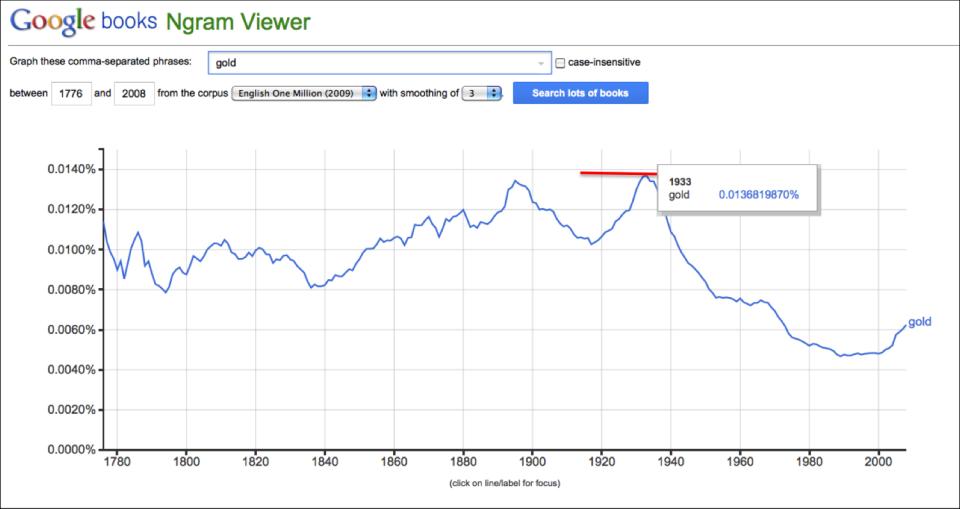

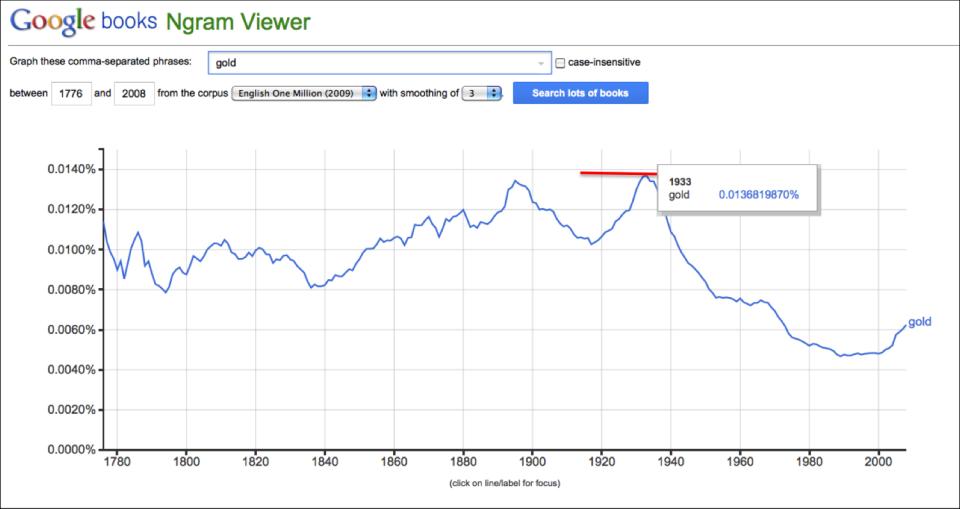

'Gold' In the English Language

I don't believe this means anything in an investment sense over some short or medium term investment horizon but worth considering nonetheless.

Via Simon Black's Sovereign Man Blog

In George Orwell's seminal work 1984, there's a really great scene early in the book between Winston (the main character) and Syme, a low-level functionary at the Ministry of Truth.

Syme is working on the 11th Edition of the Newspeak Dictionary, and he explains to Winston how the Ministry of Truth is actually removing words from the English vocabulary.

In Newspeak, words like freedom have been struck from the dictionary altogether, to the point that the mere concept of liberty would be incommunicable in the future.

I thought about this scene recently as I was testing out Google's new Ngram Viewer tool.

If you haven't seen it yet, Google has digitized over a million books that were printed as far back as 1500, and they've made the contents searchable within their own database.

The Ngram Viewer allows you to search for particular keywords. And you can see over time how prevalent the search terms were for particular years.

Out of curiosity, I searched for the term "gold" in English language books starting in 1776.

As one would expect back in the 18th and 19th centuries when gold was actually considered money, the instances of the word 'gold' favored prevalently in English language books at the time.

The trend continued into the early part of the 20th century.

But then something interesting happened in the mid-1930s. The use of the word 'gold' in English language books reached its peak... and began a steep, multi-decade decline.

Further investigation shows that the peak actually occurred in 1933. And as any student of gold in modern history knows, 1933 was the same year that the President of the United States (FDR) criminalized the private ownership of gold.

It remained this way for four decades. And by the time Gerald Ford repealed the prohibition on gold ownership, the concept of gold being money had been permanently struck from the American psyche, just as the Orwellian Newspeak dictionary had done.

By the mid-1970s (and through today), people have become readily accepting of the idea that money was nothing more than pieces of paper conjured at will by central bankers.

The good news is that, according to Google's data, there seems to be slight uptick in the number of instances of the word 'gold' in English language books over the last 10-years or so.

No doubt, this probably has a lot to do with gold's seemingly interminable rise relative to paper currency.

One can hope that the trend will hold... that more people will wake up to the reality that the central-bank controlled fiat currency system is a total fraud.

Via Simon Black's Sovereign Man Blog

In George Orwell's seminal work 1984, there's a really great scene early in the book between Winston (the main character) and Syme, a low-level functionary at the Ministry of Truth.

Syme is working on the 11th Edition of the Newspeak Dictionary, and he explains to Winston how the Ministry of Truth is actually removing words from the English vocabulary.

In Newspeak, words like freedom have been struck from the dictionary altogether, to the point that the mere concept of liberty would be incommunicable in the future.

I thought about this scene recently as I was testing out Google's new Ngram Viewer tool.

If you haven't seen it yet, Google has digitized over a million books that were printed as far back as 1500, and they've made the contents searchable within their own database.

The Ngram Viewer allows you to search for particular keywords. And you can see over time how prevalent the search terms were for particular years.

Out of curiosity, I searched for the term "gold" in English language books starting in 1776.

As one would expect back in the 18th and 19th centuries when gold was actually considered money, the instances of the word 'gold' favored prevalently in English language books at the time.

The trend continued into the early part of the 20th century.

But then something interesting happened in the mid-1930s. The use of the word 'gold' in English language books reached its peak... and began a steep, multi-decade decline.

Further investigation shows that the peak actually occurred in 1933. And as any student of gold in modern history knows, 1933 was the same year that the President of the United States (FDR) criminalized the private ownership of gold.

It remained this way for four decades. And by the time Gerald Ford repealed the prohibition on gold ownership, the concept of gold being money had been permanently struck from the American psyche, just as the Orwellian Newspeak dictionary had done.

By the mid-1970s (and through today), people have become readily accepting of the idea that money was nothing more than pieces of paper conjured at will by central bankers.

The good news is that, according to Google's data, there seems to be slight uptick in the number of instances of the word 'gold' in English language books over the last 10-years or so.

No doubt, this probably has a lot to do with gold's seemingly interminable rise relative to paper currency.

One can hope that the trend will hold... that more people will wake up to the reality that the central-bank controlled fiat currency system is a total fraud.

Until next week,

Simon Black

Simon Black

Saturday, November 23, 2013

Bubble in Gold?- A Comparison, Part 2

As a followup to my prior post, I thought it could be illustrative to show the difference between a know bubble's price action and that of gold's, again here exemplified by the GLD.Once again, I show two comparisons of the NASDAQ and gold versus their respective highs. The NASDAQ high occurring in March 2000 and gold's high in August 2011. Here however, I show the slope coefficient of the price changes over the varying time frames and using the high as the starting reference point. The first chart shows the slope of the price rise into the respective high of each asset.

And the second chart shows you the slope of the price decline relative the same high as referenced above on each asset.

What is plainly obvious in each chart is that the slope of the price rise and decline on the NASDAQ, an obvious and well established bubble, is not even in the same ballpark as the rise and fall on the price of gold. Point being, gold was just not in a bubble.

And the second chart shows you the slope of the price decline relative the same high as referenced above on each asset.

What is plainly obvious in each chart is that the slope of the price rise and decline on the NASDAQ, an obvious and well established bubble, is not even in the same ballpark as the rise and fall on the price of gold. Point being, gold was just not in a bubble.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)